Weight loss is ultimately about calories, but it’s so much more complicated than “eat less, move more,” and the metabolic changes that come along with losing weight are just one reason: it’s not just about eating less and moving more, because your body adjusts your metabolic rate depending on how much you eat and move. That introduces an unpredictable third factor into the calorie math, most notoriously in the form of “metabolic slowdown” caused by weight loss.

Unfortunately, the facts are pretty depressing: losing weight slows down your metabolism, and you have very limited options for changing that. Your body doesn’t want to lose weight; it actively fights back against the weight loss, and the more weight you have to lose, the grimmer the picture starts to look.

That was the bad news. But the good news is that it’s obviously still possible to lose weight anyway; after all, plenty of people do. Understanding the hormonal adaptations that make weight loss harder can help you make a plan for combating them, and at the very least the knowledge can help you be compassionate to your body: it’s only trying to keep you alive!

Metabolism: A Quick Refresher

First, a quick review. Your “metabolism” includes:

- Resting metabolic rate (RMR): the number of calories it would take to keep you alive if you were in a coma (pumping blood to your organs, etc.)

- Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT): the calories you burn from daily activities (because realistically, you’re not in a coma).

- Thermic effect of food (TEF): the number of calories it takes to digest your food.

So how does weight loss affect these things?

Weight Loss Reduces Body Mass

This one seems pretty obvious – no kidding, weight loss reduces your body mass. That’s the whole point. But body size is one of the biggest factors driving your overall metabolism. It takes calories to maintain all those extra pounds of fat tissue – fat might burn fewer calories than muscle, but it absolutely does burn some calories just by existing. If you have 50 or 100 pounds of extra fat, they’re burning a lot of calories every day just by being there, not to mention the extra calories you burn carrying them around from place to place.

When you lose weight, your resting metabolic rate goes down, because there’s less of you to maintain. Your non-exercise activity thermogenesis goes down because you’re spending fewer calories every time you move.

That part is pretty obvious, and nobody’s really disputing it. But if body mass were the only factor affecting your metabolism, you could do an experiment like this:

- Go for a walk pre-weight loss. Say you burn 100 calories on your walk.

- Lose 50 pounds.

- Put on a 50-pound weight vest and go for the same walk that you went on before losing weight. You should burn 100 calories, right? You’re carrying around the same weight in total!

But that’s not how it works. That experiment has actually been done, and weight-reduced people burn fewer calories from exercise even when they’re wearing weights that bring them back up to their pre-weight-loss weight.

When you lose weight, your resting metabolic rate goes down disproportionately to your body mass. This change rebounds a little bit in maintenance, but not completely: a person maintaining a lower weight after weight loss still has a slower metabolism than a person who has always been that weight.

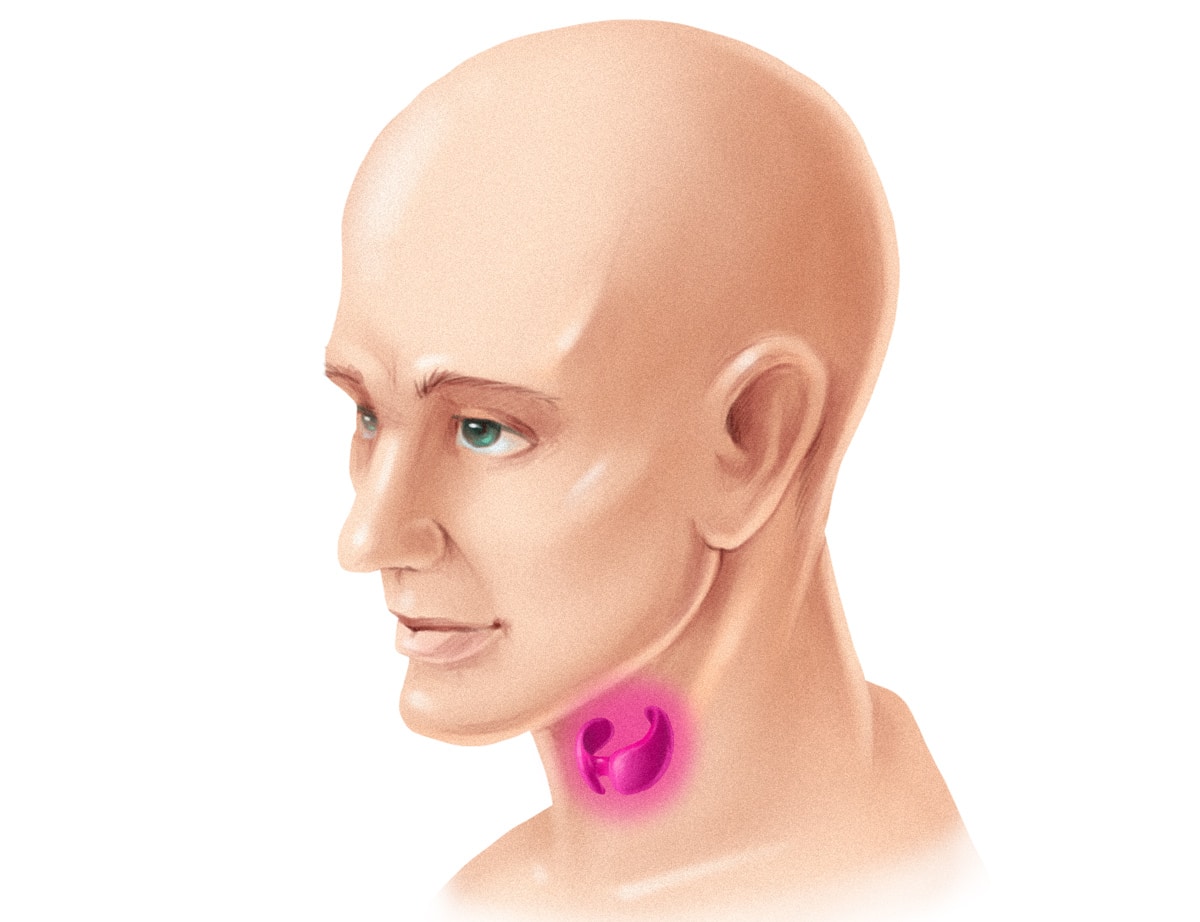

Is it the Thyroid Hormones?

One big culprit is the thyroid. The thyroid is a very complicated little gland, but among its many functions is control of the metabolic rate. Weight loss from dieting (weight-loss surgery is a whole different kettle of fish and not part of the discussion here) reduces levels of the thyroid hormone T3, which can affect your metabolism in all kinds of ways.

For one thing, it affects the way you burn calories to generate body heat. In fact, unusually high T3 may be one consequence of obesity, one of the ways that your body tries to maintain energy balance (by balancing out the increase in calories consumed by burning more to create heat). This is one reason why so many obese people feel uncomfortably warm when thin people are just fine. Unfortunately, the process of weight loss and the reduction in T3 makes your body stingier with the calories it burns for heat, which might make you more comfortable in the summer time but also reduces your resting metabolic rate.

Another point in favor of the thyroid theory is that T3 supplements do help people lose weight, albeit at the cost of “tachycardia, arrhythmias, fatigue, irritability, loss of bone mass, and muscle wasting usually accompanying thyroid hormone excess” (source). In other words, effective, but not really worth it.

There's a problem with the thyroid hormone theory, though. Low-carb diets reliably reduce T3 levels, but they don't affect resting metabolic rate.

- This study found that T3 decreased significantly faster on a low-carbohydrate/low calorie diet than a low-fat/low calorie diet, but resting metabolic rates were basically similar.

- This study also found that resting energy expenditure did not differ by diet composition (they tried a bunch of different diets with various percentages of fat, protein, and carbs).

What's going on with this? It could be one of several different things - there's more to thyroid hormones than T3, calorie restriction confounds the problem of distinguishing between low-carb and low-fat diets, and there's always the problem of subjects who don't adhere to the study diet at all. But one other potential answer is muscle efficiency.

T3 affects much more than your resting metabolic rate. Just to take one example, it may affect your mitochondria, the cells that produce energy for your body. Reduced levels of T3 can make your mitochondria more efficient, so they waste less energy and basically do more with less. This means that it takes fewer calories to do every single thing throughout the day, from brushing your teeth to making tea to cooking dinner. That’s great if you’re actually in danger of a famine (which is in fact what your thyroid thinks is going on), because it preserves your energy stores (aka fat tissue) and slows down the process of starving to death. But it’s not so great if you want to lose weight, because eating through your stored energy reserves (fat tissue) is exactly what you’re trying to do!

It's also possible that the increase in muscle efficiency is caused at least partially by other factors as well, but T3 likely has something to do with it, and in any case, the result is the same: a reduced weight that's hard to maintain.

Summing it Up

Weight loss is hormonally difficult, which is unfair and very unhelpful in the modern world, but it doesn’t do any good to pretend these problems don't exist! Hormonal changes during weight loss slow down your metabolic rate even more than can be explained by the loss of fat tissue, and make your muscles more efficient so that they burn less calories doing everything from your actual workouts to carrying your laundry across the room. This would all be great if you were actually in any danger of famine, but considering that you (probably) aren't, it's not terribly helpful and it can be very frustrating.

Of course, it's always important to remember that there's a lot of individual variation here - some people might have such a small metabolic reduction that they barely notice it, while other people might struggle a lot. If you're in the second group, check back next week for some practical tips on minimizing the metabolic consequences of weight loss with diet, exercise, and lifestyle strategies.

Leave a Reply