Getting an adequate amount of exercise is one of the best things you can do for your body. That much we know for sure. Exercise builds muscle; it increases insulin sensitivity; it improves balance and coordination…the benefits are almost endless. And since only so few Americans ever get any exercise at all, most of the public-health messages are focused on doing more of it. But exercise isn’t just a limitless good – there’s a point when “healthy” shades into “too much,” and you can actually improve your health by doing less of it.

There are all kinds of ways of figuring out when this point is. Some people can just “feel it” when they could use a rest; others use various metrics (their lifting log, their mileage count, their coach’s suggestion) or simply take a rest day every so often regardless of whether they “feel it” or not. But from a scientific perspective, one of the most interesting ways to look at it is from the immune perspective.

A healthy amount of exercise provides an overall “boost” to the immune system (to the extent that you can really “boost” something as complex as immunity). But did you know that overdoing it actually reduces immune function? Endurance athletes (like marathon runners, distance swimmers, and triathletes) have notably depressed immunity, especially when it comes to upper respiratory tract infections (like colds). And when these elite athletes do get colds, their symptoms tend to last longer and be more severe.

These runners perform at higher levels than the rest of us, but the tradeoff is their health. And unless you’re an elite athlete, you don’t want to make that tradeoff. Tracking the immune system lets you see when you’re sacrificing optimal health for performance – and how to stay on the “health” side of the line.

What kind of exercise lowers immunity, and why?

It’s pretty clear that not just any kind of exercise produces a noticeable immune depression. This study really says it best. The researchers examined three groups of people: elite athletes, recreational athletes, and sedentary controls. Their results:

- The elite athletes had the most upper respiratory issues (66% got sick).

- The couch potatoes were next (45% got sick).

- The recreational athletes were the healthiest (22% got sick).

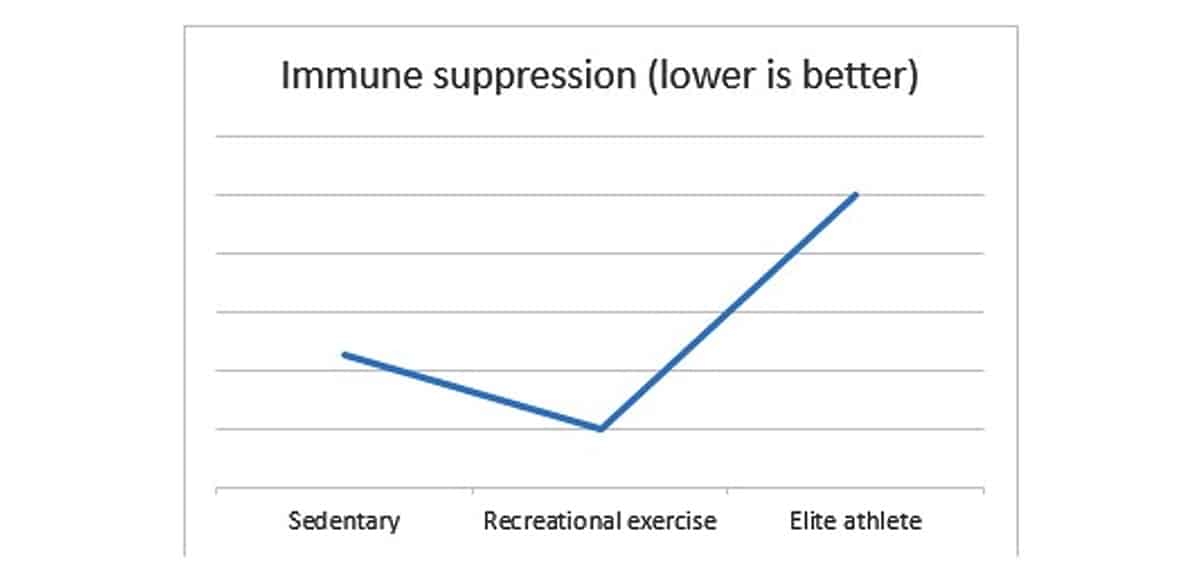

All kinds of other research has found the same thing, so exercise scientists tend to use a J-shaped curve to model the immune effects of exercise. It looks like this:

So moderate exercise is significantly better for you than no exercise at all, but there’s a point where that benefit stops and overtraining sets in. This review gets a little more specific about what kind of exercise produces the immune-suppressant response:

- Relatively long workouts (1.5 hours or more), especially without refueling during the workout.

- A reasonably high intensity, but not excessively difficult (since you have to be able to keep it up for a while).

- An inadequate recovery period between workouts.

So how do these factors combine to result in a post-race case of the sniffles? There are all kinds of theories about this. It’s clear that exercise does cause significant hormonal changes. Specifically, it raises the levels of norepinephrine and cortisol, two “stress hormones” that tend to suppress the immune system. The hormonal changes of exercise cause the numbers of immune cells (including leukocytes, or white blood cells) to drop immediately during and after the workout.

Exercise also decreases levels of an amino acid called glutamine, which plays an important role in the immune system. So it’s reasonable to speculate that the dip in immune function might be somehow related to glutamine levels as well.

All these are completely plausible hypothesis, but we actually have very few studies conclusively linking any one of them in particular to any measurable sign of infection. And interestingly enough, in one study, a lot of the symptoms of upper respiratory infection were not actually caused by any identifiable pathogen, suggesting that something more than the immune system is at work here. The same review from above concludes that a variety of factors are probably responsible:

- Airborne pathogens: when you run outside, you get exposed to all kinds of stuff floating around.

- Physical stress on the lungs and throat: breathing hard (especially in extreme weather conditions) dries out the airway.

- Psychological factors: elite athletic performance is mentally taxing, and when your brain is exhausted, you’re more likely to feel sicker.

- Nutrition: overtraining is often accompanied by underfeeding. And if your body isn’t fueled right, it can’t do a very good job of defending itself against anything.

All of these stressors create perfect conditions for an infection, or just a day of feeling lousy, to take advantage of the exercise-weakened immune system.

Diet, Exercise, and Immunity

So how can you avoid a workout-induced case of the sniffles? It's pretty simple: don't overtrain, and don't undereat. Take a look at the factors that cause immune suppression (long, high-intensity workouts with inadequate recovery), and do the opposite: go for shorter workouts, less often, and make sure you’re recovering sufficiently in between.

The tipping point is different for every individual, but your body will let you know when you've gone too far - you just have to listen to it. If you're feeling physically or emotionally exhausted from your workouts, dreading the gym, plying yourself with coffee every morning to stagger onto the treadmill, or constantly nagged by little aches and pains that never go away...you're overtraining! This article has some tips to help you diagnose a potential case of overtraining; if this is you, it might be time to take a rest week, or start incorporating more rest into your weekly routine.

But sometimes you have to (or want to) train hard. So how else can you minimize the damage?

This article takes a hard look at the exercise-associated dip in immune function, and what kinds of dietary interventions might reasonably show promise for treating it.

Carbs are clearly essential: immune cells need some glucose to function properly. Several studies have shown that overtraining on a low-carb diet (7-11% carbohydrate) produces a magnified change in the immune system. This just suggests what we all knew already: athletes need enough carbohydrates to keep themselves fueled properly!

Protein is also important. But supplementation with glutamine (a specific amino acid widely thought to improve immune function) hasn’t shown much benefit. It’s true that glutamine levels drop with extensive endurance exercise, but the one study showing benefits from glutamine supplementation was in extreme long-distance runners (marathon and ultramarathon runners), a finding which hardly applies to most recreational athletes.

Dietary fat hasn’t been studied much; the studies that do exist show no significant difference between a high-fat and medium-fat diet, although a very low-fat diet (less than 15% fat) is a bad idea. Not that a low-fat diet was much of a risk on Paleo anyway!

Ultimately, the authors of the study concluded that “evidence for a beneficial influence on immune parameters in athletes from single macronutrients is scarce and results are often inconsistent.” In other words, looking for a single “magic bullet,” whether it’s carbs, protein, fat, or micronutrients, is misguided and unlikely to be useful.

This study backs that up on the micronutrient front: deficiency of iron, zinc, or Vitamins A, E, B6, or B12 is associated with impaired training, but there’s no evidence that high-dose supplements will give you any improvement. Once you have an adequate intake, increasing the amount just won’t help.

The lesson overall: even the best diet will not save you from hitting it too hard at the gym. If you’re deficient in something (whether it’s a specific vitamin or something as simple as “enough calories,”), you’re in for double trouble, but you cannot “compensate” for overtraining by just eating more or different food.

Conclusion

From putting immune function under the microscope like this, we can clearly see the U-shaped benefits curve of exercise: some is good, more is not always better, and too much is very bad. The types of exercise that impair immunity (very long workouts at medium-high intensity and inadequate rest days) give us a clue what to avoid to stay healthy.

This can be hard to hear for dedicated gym-goers who are used to the no-excuses, just-do-it model of training every day whether they feel like it or not. But the evidence is clear: this simply isn’t good for you. It’s not good for your health; it’s not good for your performance. So if you’re constantly feeling beat-down by your workouts, or if you’ve been getting sick a lot lately, try sleeping in instead: you might be surprised by how much better you feel afterward.

Leave a Reply