By last count, 55% of Americans want to lose weight – and while body image and the desire to look attractive certainly play a role in this, a big part of it also revolves around health. We all know that being overweight is unhealthy: it’s a strain on your joints, it’s a risk factor for metabolic diseases like diabetes, it’s a contributing factor to asthma, reproductive disorders, sleep apnea, hypertension, and just about everything else under the sun. Right?

Well, sort of. If you take a hard look at the actual evidence, it’s not quite as clear-cut as “overweight = unhealthy.” What’s really unhealthy are behaviors like a sedentary lifestyle, never exercising, and eating lots of junk food – these are behaviors that tend to be associated with overweight and obesity for fairly obvious reasons, but the association is far from perfect. Many fat people do exercise, many fat people don’t overeat, and we all know at least one person who by rights ought to weigh 400 pounds but stays thin through some miracle of metabolism and good genetics. And as it turns out, those skinny couch potatoes are significantly less healthy than their overweight friends who go for a walk every day and eat their spinach.

Not convinced? It’s understandable: most of us are so used to taking weight as a proxy for health that we don’t even think to question it. But take a look at some of the actual evidence, and it’s pretty clear that this “shortcut” is really just a stereotype: behavior, not weight, is what really makes us healthy (or not). There’s nothing wrong with having a weight-loss goal in addition to your health goals, but if you’re feeling discouraged by a rough patch in your weight loss efforts, remember: healthy behavior is helping you even if the scale doesn’t budge.

Healthy Habits Beat Weight in Predicting Risk

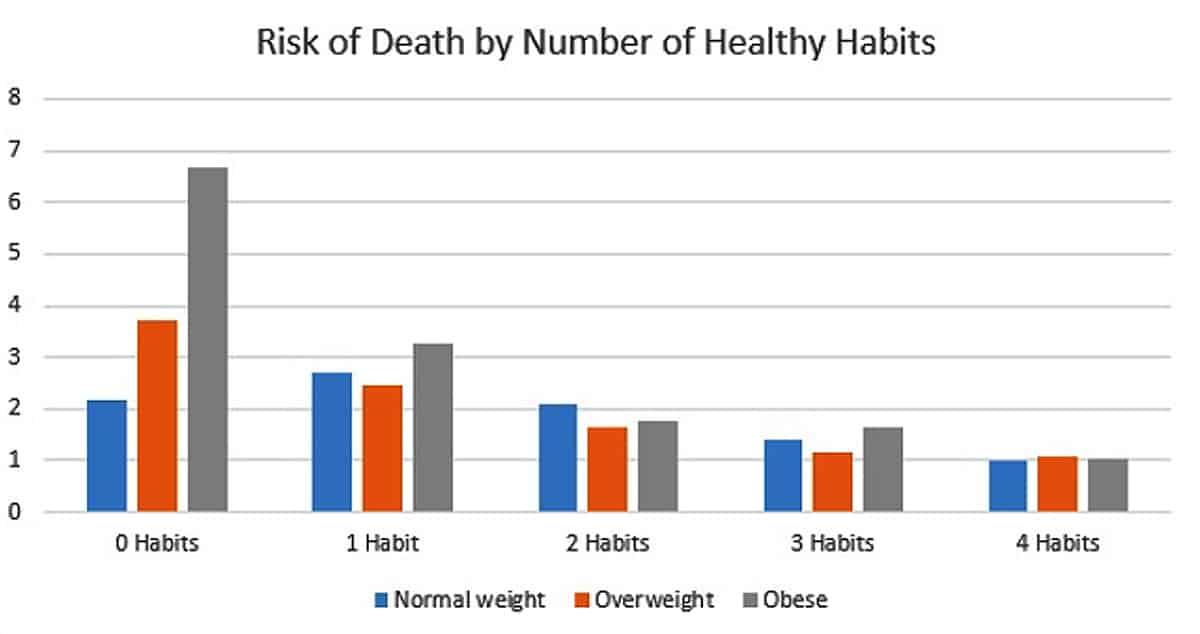

This study looked at the influence of four different “healthy habits” (eating 5 or more servings of fruits and vegetables a day, moderate drinking, not smoking, and exercise) and how well they predicted death from all causes for normal weight, overweight, and obese adults. They expressed their results as a “hazard ratio.” Normal-weight people with all 4 healthy habits scored a 1, and all other groups were scored relative to them. The greater a group’s risk of death, the greater their score. Take a look at the numbers:

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that people with 4 healthy habits were the healthiest, but take a good hard look at the data: among people with healthy habits, obese and overweight people were just as healthy as normal-weight people.

The big difference, of course, is that among people with 0 or 1 habit, the obese and overweight had a much higher risk. But nobody in these groups is healthy, including the thin people! What this study really shows is that healthy habits, not BMI, predict big-picture health.

Health Improves Before or Without Weight Loss

It’s a documented phenomenon in diet research: subjects put on “healthy” diets typically show improvement before they lose any substantial amount of weight – and even if they don’t lose any weight at all. This suggests that it’s not the weight loss per se that causes the health improvement; it’s the behaviors that lead to the weight loss.

A few examples of this:

- In this study, researchers put obese subjects on a diet that was very close to Paleo (the “Spanish Ketogenic Mediterranean Diet,” focusing on olive oil, fish, fruits, and vegetables). After 12 weeks, 77% of the subjects were still technically “obese,” but all of them were entirely free of metabolic disorders, and their blood lipids, blood pressure, and blood sugar levels had all improved dramatically. The subjects did not have to reach a healthy weight before their health improved.

- In this study, subjects were deliberately kept at a stable weight, but a diet rich in fruits and vegetables still improved blood pressure compared to a plant-deficient diet.

- In this study, weekly exercise improved blood lipid profiles in overweight people even when subjects showed minimal weight change (and were in fact instructed to maintain their current weight)

If it really were the weight loss that led to these improvements, subjects in these studies wouldn’t have seen any changes – since they didn’t lose weight. But they did see significant health improvements, suggesting that the weight is a symptom of health status, not a cause of it.

Weight Loss Doesn’t Always Improve Health

We tend to talk about weight loss as though it were some kind of magical cure-all for all the problems associated with (note: not caused by!) overweight and obesity. But take a look at some of the data:

- In this study, loss of 15% or more of body weight (which would be 45 pounds for a 300-pound person) was associated with an increased risk of death for both sexes. In women, even a smaller loss of 5-15% was dangerous.

- In this review of 9 studies, 2 found that intentional weight loss improved health; three found that it diminished health, and four found no association at all.

It’s important not to misinterpret these studies. The first uses data from the NHANES survey, which covers all American adults. That means that the “weight losers” are most likely chronic yo-yo dieters (since that’s the typical pattern of dieting in the United States), and yo-yo dieting is a very different animal from long-term weight loss that stays lost. But still, at least one message is clear: weight loss per se does not necessarily improve health if it’s not gone about in a healthy and sustainable manner. Again, this implies that it’s the healthy behaviors, not necessarily the number on the scale, that really make people healthier.

This is particularly clear when you look at studies of weight loss without behavior change (using surgical methods):

- This study looked at patients who underwent liposuction. Despite losing a lot of fat, they had no improvement in insulin sensitivity or any other metabolic markers.

- This study started with the theory that the stress of the liposuction itself might have masked the beneficial effects of the fat loss. But even 4 years after losing 21 pounds of body fat via liposuction, subjects had no improvement in metabolic risk factors like blood pressure, insulin resistance, and cholesterol numbers.

To back this up even further, this review of studies that focused on health, rather than weight loss, found that they did indeed improve health (including psychological and mental health) despite showing less weight loss than studies focused on dropping pounds at all costs.

When you put it all together, the evidence seems fairly clear: body fat is the symptom, not the problem. It’s unhealthy behavior that causes negative health outcomes, and when you change a person’s behavior, you change their disease risk regardless of what happens to their weight.

The “Healthy Obesity” Studies

Taking this even further, a number of studies have proposed the radical idea that there might be a certain subset of “healthy obese” people: people who have excess body fat but no health problems to go along with it. If these people really do exist in significant numbers, it’s obviously not the extra body fat that causes health problems associated with obesity.

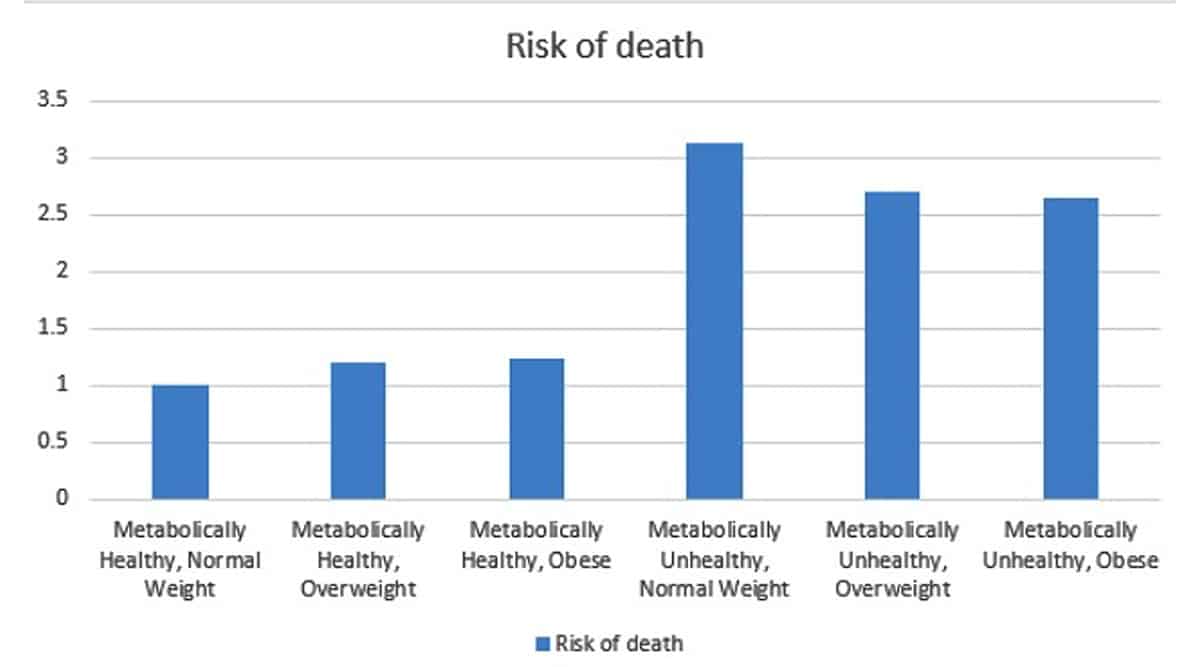

Most recently, there’s this study, which made waves when it first came out. Researchers tried to separate the risk of being metabolically unhealthy (insulin resistant or diabetic) from being overweight. What they found was very surprising: take a look at the relative risks of the six categories of people:

You’re not seeing things here: statistically speaking, a thin person with a metabolic disorder is 2.5 times more likely to die than an obese person who eats healthy food and exercises.

But wait…just how relevant is this? After all, aren’t most obese people metabolically unhealthy? And aren’t most thin people metabolically healthy? Sure, there might be a tiny number of the “healthy obese,” but the vast majority of the time, obesity is a sign of metabolic damage…right?

Nope, not really. Metabolic syndrome is more common among the overweight and obese, but it affects normal-weight people. According to the latest CDC numbers, about 34% of Americans have metabolic syndrome, including 7-9% of underweight and normal-weight people – that’s a substantial number of people who are thin on the outside, but sick on the inside. And 67-70% of the overweight, and 35-55% of the obese have no metabolic symptoms whatsoever (the ranges are due to sex differences).

That’s a whole lot of “healthy obese” people who don’t have a significantly higher risk of CVD or death than their thin counterparts!

This study tried to qualify “healthy obese” by another measure: cardiovascular fitness. And their findings were almost the same: 46% of the obese people were “metabolically healthy;” these healthy obese subjects were fitter (as measured by a treadmill test) than their metabolically unhealthy peers, and were not at greater risk for cardiovascular disease and cancer than “normal-fat” people. The researchers concluded:

Once fitness is accounted for, the metabolically healthy but obese phenotype is a benign condition.

So What Does All This Mean?

Let’s start with what it doesn’t mean. Nothing here suggests that whatever weight a person happens to be at is the healthiest weight for them. It doesn’t mean that weight loss is a “bad” goal. It doesn’t mean that Paleo (or any other healthy diet) won’t help you lose weight; if you’re overweight, it probably will. And it doesn’t mean that being overweight or obese is healthier than being at a normal weight.

What it does mean is this:

- Weight is not a sign of health. Some thin people are very sick; some overweight people are perfectly healthy.

- Weight loss does not automatically improve health. Only healthy, sustainable weight loss does that: yo-yo dieting is actually bad for you. Losing 20 pounds and keeping it off beats losing 30 pounds and regaining in 6 months.

- Healthy behaviors do improve health – for all people, regardless of size.

The logical conclusion is that it’s time to focus less on weight and more on changing behavior: establishing healthy habits, eating home-cooked, nutrient-dense whole foods, and finding some enjoyable way to be active. Weight loss is not always under your control. There will always be setbacks, disappointments, and "bad days" when scale just isn't cooperating despite all your hard work. But your behavior is always under your control, and the benefits of those behavior are real even if you're going through a rough patch in your weight loss journey (or if you never had any weight to lose in the first place).

In all likelihood, healthy behaviors will result in weight loss for people who have weight to lose. But the weight loss is a symptom of better health, not a cause of it.

This is an encouraging fact to keep in mind in the season of weight-loss resolutions and the inevitable struggles with the occasional setback, stall, or even regain. Eating healthy will bring you benefits independent of weight loss. Focus on all the other benefits of good diet and lifestyle habits, and you’ll be less tempted to quit when you come to a bump in the weight-loss road. And ultimately, you'll stand a much better chance of achieving the weight loss you're looking for, in a healthy and long-term sustainable way.

Leave a Reply