When it comes to criticizing the modern diet, two of the biggest Paleo bones to pick are autoimmune disease and metabolic disease (the cluster of problems including obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, hypertension, PCOS, and others). The typical Paleo story is that the same foods cause both problems, but for different reasons – for example, refined flour might contribute to autoimmune disease because it contains gut irritants, and also contribute to metabolic disease via carb/calorie overload.

There's always been some overlap - for example, it's common knowledge that autoimmune hypothyroidism can affect weight. But some new research suggests that it works the other way, too: metabolic diseases can provoke autoimmunity. Under this model, the distinction between autoimmune and metabolic diseases gets very blurry, which raises important questions about how people should eat to manage those problems.

Autoimmunity in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes

A recent study pointed out that obesity is associated with all kinds of autoimmune diseases. They connected obesity to…

- Multiple sclerosis

- Lupus

- Crohn’s Disease and ulcerative colitis (Inflammatory Bowel Disease)

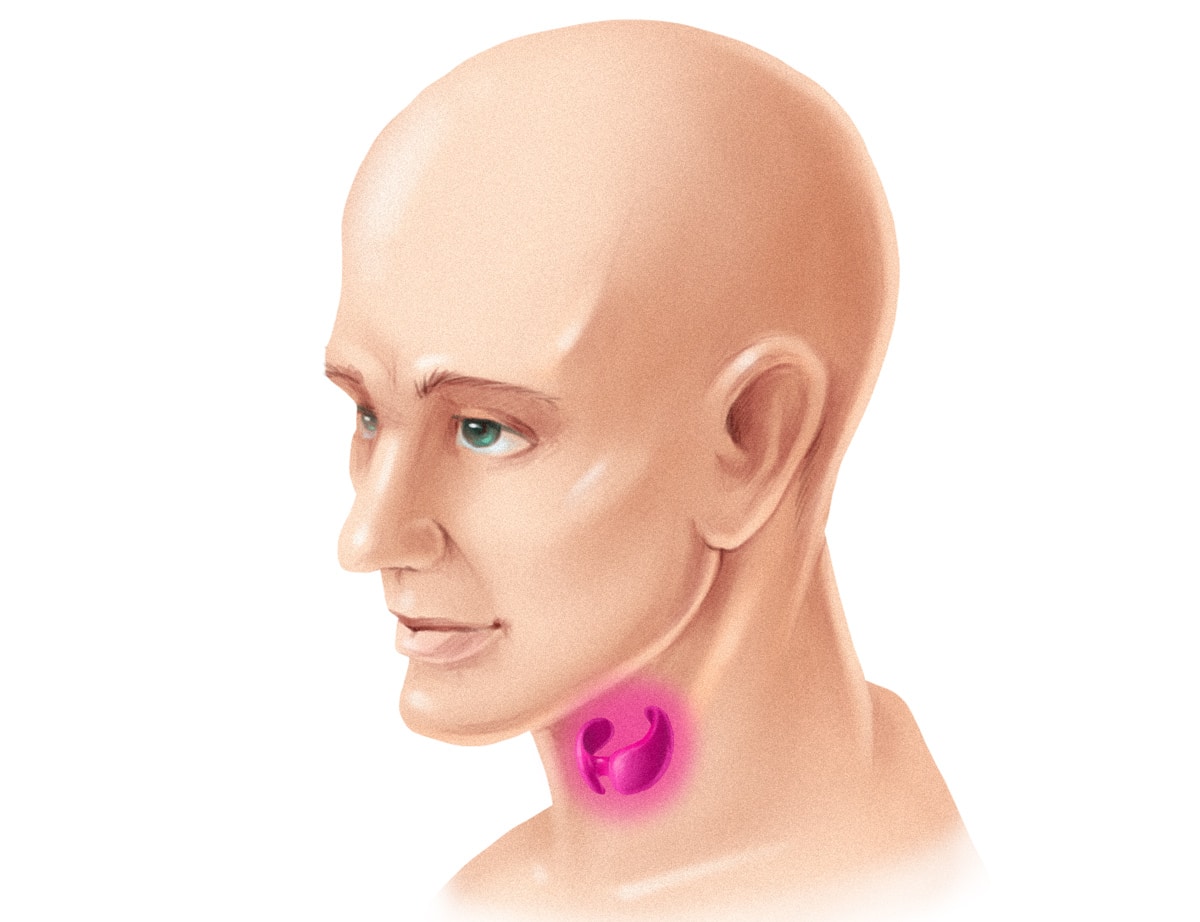

- Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis

- Type 1 Diabetes

The authors’ explanation started out with the fact that fat cells don’t just hang out on your body storing energy. They’re metabolically active in their own right, and in particular, they control some powerful inflammatory messengers. The authors of the study suggested that inflammatory signals from fat cells affects the immune response, which makes obese people more prone to developing autoimmune reactions.

Other recent research has examined Type 2 Diabetes as a disease with an autoimmune component. Type 2 Diabetes is the type of diabetes usually blamed on lifestyle (Type 1 or "juvenile diabetes" is the one that everyone knows is autoimmune). This study summarized some of the evidence for an autoimmune component in Type 2:

- Insulin resistance in fat tissue is related to a type of immune cells called T cells. Obese mice with insulin resistance have low levels of regulatory T cells in their fat tissue, and introducing regulatory T cells improves their insulin sensitivity.

- Patients with Type 2 Diabetes have higher levels of inflammatory markers, and most people agree that inflammation contributes to the development of insulin resistance.

- Inflammation is a risk factor for autoimmunity, as is obesity (which often tags along for the Type 2 Diabetes ride).

- New evidence has shown that immune-mediated damage to the pancreas isn’t just a feature of Type 1 Diabetes; it’s also part of Type 2.

To quote the authors:

“Accumulating data support the concept that not only are islet autoreactivity and inflammation present in T2D, but also islet autoimmune disease. Moreover, the development of islet autoimmune disease appears to be one of the factors associated with the progressive nature of the T2D disease process.”

This study even described a theory that Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes are “the same disorder of insulin resistance set against different genetic backgrounds.” In both forms of the disease, insulin resistance causes the autoimmune destruction of beta cells in the pancreas – it’s just that the particular progression of the disease depends on individual susceptibility to autoimmunity.

Another potentially related issue is hormone levels. This study found that women with PCOS (a hormonal metabolic disease marked by sex hormone imbalances and insulin resistance) had a much higher prevalence of markers for autoimmune thyroid problems than healthy controls. Many women with PCOS also have antibodies against their own ovarian tissue, which suggests another way that autoimmunity could be involved.

The authors’ explanation was an imbalance in sex hormones, specifically too much estrogen and not enough progesterone: estrogen and progesterone both affect the immune system, and estrogen tends to stimulate the immune response, so too much estrogen could over-stimulate the immune system and make the woman susceptible to autoimmunity.

This is relevant to obesity because PCOS often goes along with obesity, and because many obese people (men as well as women) have high estrogen levels even without PCOS.

All of this doesn’t necessarily spell death for the idea of “healthy obesity.” Someone who has an elevated number of fat cells but doesn’t have a high degree of inflammation or hormonal dysfunction might not actually be at any increased risk of autoimmune disease according to this model – and those people do exist (although they’re rare, because many causes of obesity also tend to be inflammatory and hormone-disrupting).

It also does raise the question of people who are thin by BMI but metabolically sick – the so-called Metabolically Obese Normal Weight (MONW) group, which you might know better as “skinny-fat.” They have higher levels of inflammation than metabolically healthy people: do they also have a higher risk of autoimmune diseases?

A Vicious Cycle?

The authors of the diabetes papers above noted that the autoimmune response in the pancreas is one reason why diabetes is a progressive disease: insulin resistance provokes an autoimmune reaction in the pancreas, which causes the destruction of beta cells, which makes the insulin resistance worse, and so on. The authors of the PCOS study explained that hypothyroidism can make PCOS worse, which also raises the possibility of a vicious cycle.

Could the same be true of obesity? It sounds plausible: the thyroid is a major player in determining metabolism. If an inflammatory response in fat tissue promotes autoimmune hypothyroidism, then the resulting metabolic slowdown might make it easier to gain more weight. But that’s just an idea; none of the studies actually discussed it.

What can We Conclude from All This?

Obviously not every person with an autoimmune disease has obesity or Type 2 Diabetes – Celiac Disease, for example, can cause malabsorption of calories and nutrients in the gut, so patients with untreated Celiac often need to gain weight, not lose it. But obesity and other metabolic diseases may also have an autoimmune component related to inflammation and insulin resistance (often but not always accompanied by extra weight). What does that mean for Paleo specifically?

Well, for one thing it’s a new perspective on the perfect storm of overabundant, gut-irritating junk food that we all live in: refined carb overload doesn’t “just” cause metabolic disease and gut irritants don’t “just” contribute to autoimmunity; it’s all connected.

The potential for a vicious cycle (metabolic diseases that contribute to autoimmunity, which makes the metabolic disease worse…) also poses another problem for the idea of calorie reduction as the solution to obesity and related metabolic diseases. Regardless of the reason why someone has an autoimmune disease, if they now have autoimmune problems that are contributing to their disease, then suppressing their weight with calorie restriction may be possible, but it might not actually do anything to fix the underlying problem, and it may also be unnecessarily difficult.

On the other hand, if someone has autoimmune problems that are contributing to their obesity (or diabetes, or anything else), and instead of counting calories they pick up an anti-inflammatory lifestyle and diet behaviors and eliminate any foods that trigger their autoimmune flares (if those foods exist), then that might be more helpful. The connection between autoimmunity and metabolic disease is another argument for the idea that diet quality matters, and there’s more to weight-related health issues than how many calories you eat.

Leave a Reply