Friendly gut bacteria are an important part of your health – they keep the digestive system running smoothly, help you break down your food and absorb nutrients from it, and support healthy immune function and metabolic regulation. Unfortunately, these beneficial gut flora have a gang of sinister cousins: bacteria like Streptococcus and Eschericia coli that can cause serious diseases. To fight diseases caused by these bacteria, doctors often prescribe antibiotics, which work in several different ways. While effective against most kinds of bacteria, antibiotics are problematic from a long-term point of view because they’re essentially the medical equivalent of area bombing. They do kill harmful bacteria, but they also kill everything else in your gut at the time, including all the beneficial gut flora that you need for proper digestion.

This means that anyone interested in long-term gut health should be as cautious around antibiotics as they are around other potentially inflammatory gut irritants like grains, legumes, and any processed food products. Antibiotics are occasionally necessary (better to have damaged gut flora than to die of tuberculosis), but use them sparingly, and always take the proper steps to minimize the damage during and after your course of medication.

How Antibiotics Work

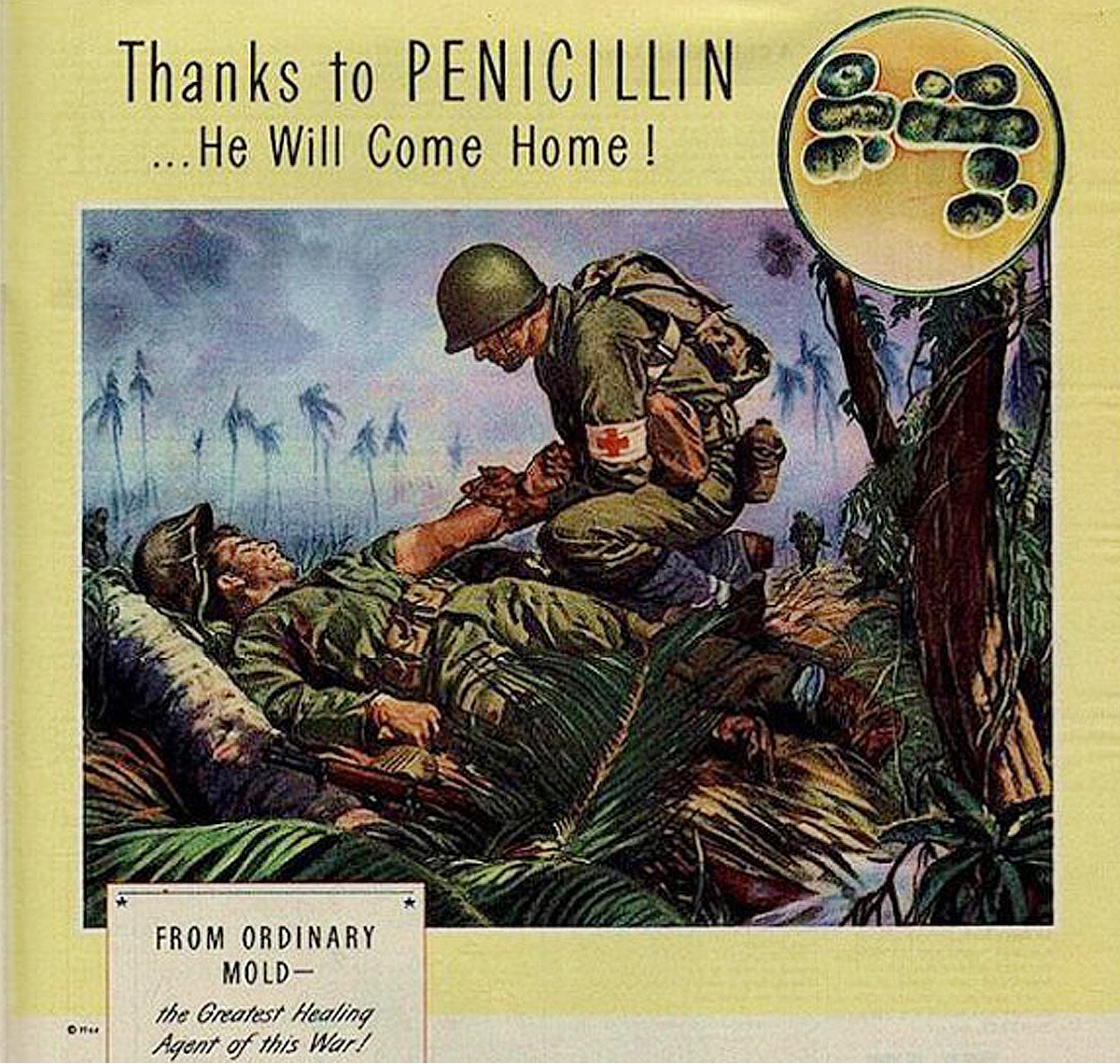

Some forms of antimicrobial medications have been used for thousands of years, but the first effective antibiotic (and still the best-known) is penicillin, discovered by British scientist Alexander Fleming in the 1920s. Fleming stumbled upon the realization that a mold called Penicillium could kill bacteria in his petri dishes; in further experiments, he isolated the substance that the mold produced, which he named penicillin. Spurred by military need during the Second World War, penicillin got its first field test in military hospitals (drug manufacturers had to make a massive effort to produce enough for the D-Day invasion), and became available to the public by the end of the war. His work in developing the world’s first antibiotic earned Fleming the Nobel Prize in 1945.

Since Fleming’s discovery of penicillin, scientists have produced more than 150 different kinds of antibiotics, either by extracting them from natural sources or by synthesizing them in a lab. Broadly speaking, an antibiotic is any biological compound that kills or inhibits the growth of bacteria. Antibiotics can be sorted into several overlapping categories. Bactericidal antibiotics kill bacteria in one of several different ways; bacteriostatic antibiotics prevent them from multiplying. Antibiotics can be further categorized according to what part of the bacteria they attack: the cell membrane, the cell walls, protein synthesis, nucleic acid (DNA) synthesis, or the metabolism. Penicillin, for example, attacks the cell walls. Doctors can also classify antibiotics according to the bacteria they fight: a drug may be broad-spectrum (effective against many different bacteria) or narrow-spectrum (effective only against one or two types).

Although not all antibiotics are effective against all bacteria, this diversity gives doctors a wide range of choices, and some leeway to select the drug best suited to the specific patient and disease.

Dangers of Antibiotics

Antibiotics were hailed as “miracle drugs” in the 1940s, and to a cranky child with a case of strep throat or tonsillitis, they really can seem like magic: take one or two pills, and in a few hours the pain is gone. Unfortunately, the long-term consequences aren’t so rosy. The immediate danger of antibiotics is the danger they pose to your gut flora. A course of antibiotics will decrease the diversity of bacteria in your gut, and weaken the strains that remain. Gut flora damaged this way are not as effective in supporting immune health, which can potentially lead to a vicious cycle where antibiotics compromise your immune system, so you get sick more easily and need more antibiotics. Immune health is far from the only benefit of healthy gut flora: after a course of antibiotics, these friendly bacteria are also less effective at promoting digestion and regulating your metabolism. In other words, antibiotics have the potential to reverse all the beneficial effects of a gut-healthy Paleo diet, leaving you more likely to gain weight, struggle with digestive problems, and get sicker.

Wiping out your gut flora with antibiotics can also lead to less savory characters sweeping in to take their place. The best example of this is Clostridium difficile (C. diff), an antibiotic-resistant “superbug” that causes diarrhea, stomach upset, and other digestive problems. Even eliminating harmful bacteria can potentially cause problems. A vaccine for pneumonia, for example, prevents the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae from colonizing an individual. Researchers thought that preventing pneumonia this way would be a great benefit, but in fact S. pneumoniae is a strain commonly found in healthy people, and removing it can make way for other, more harmful bacteria to take its place.

For newborns, antibiotics can be especially damaging because a newborn has no pre-existing gut flora. Babies born vaginally get their first gut flora as they pass through the birth canal; all babies also receive bacteria from their food (one of the reasons why breastfeeding is ideal). Antibiotics given to a pregnant woman can prevent the fetus’ gut flora from developing normally, leading to immune problems after birth. Antibiotics accompanying a C-section can compound the problem: one study found that infants born by C-section with antibiotics had disrupted gut flora for six months afterwards. Antibiotics given after birth are also problematic, because they disrupt the normal colonization pattern of beneficial bacteria, and can potentially set the baby up for chronically poor gut health later. Thus, meddling with the natural balance of microbes in the human body is a risky proposition with several poorly-understood side effects.

Quite aside from the damage to your gut flora, taking too many antibiotics also causes a long-term public health problem: antibiotic resistance. Essentially, antibiotics function as an agent of natural selection. When bacteria are first introduced to an antibiotic, the drug kills all the weaker members, leaving the strongest bacteria to survive and reproduce. Bacteria and antibiotics dance a constant evolutionary tango around each other, as each side increases its strength and the other responds. Unfortunately, bacteria have a superweapon in this fight: they can easily exchange genes, even across different species, so one antibiotic-resistant species can pass on its resistance genes even to a species that has never yet encountered that antibiotic. Humans can artificially enhance antibiotics to increase the potency of the naturally occurring forms, but bacteria will eventually adapt even to these stronger medications, requiring antibiotics to pack more and more of a bacteria-killing punch to stay effective.

To date, an increasing number of bacteria have developed multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains that no longer respond to standard antibiotics. To fight these diseases, doctors have to prescribe stronger and stronger medicines – and the stronger the weapon, the greater the collateral damage to your body. Hospitals (crowded spaces full of sick people with compromised immune systems taking all kinds of antibiotics) are prime locations for antibiotic-resistant infections to flourish, but MDR bacteria can also spread just like ordinary bacterial infections. So far, particularly worrisome MDR bacteria include MRSA (Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, a form of staph infection), totally drug-resistant tuberculosis, and drug resistant strains of E. Coli, pneumonia, and malaria.

Antibiotics have a laundry list of other side effects that vary widely from person to person. Allergies to antibiotics are less common, but they do occur, sometimes with very unpleasant symptoms. While they can save lives, antibiotics have serious consequences; they aren’t a harmless “wonder drug.”

Avoiding Antibiotics

Since antibiotics have the potential to cause such nasty side effects, avoiding then whenever reasonably possible is a good rule of thumb. The easiest way to reduce the dangers of antibiotics is to reduce your need for them: eating a nutritious Paleo diet and getting enough sleep will boost your immune system and make you less likely to get sick in the first place. Many healthy adults can go for years without getting a serious bacterial illness or infection.

You should also do everything possible to reduce unnecessary contact with antibiotics outside of medication. One common way that many people are needlessly exposed to antibacterials is household cleaning products. Dishsoap, laundry detergent, hand soap, lotion, and all kinds of cleaning sprays proudly boast about their antibiotic properties: finding a brand of soap that isn’t antibacterial is harder than finding one that is. Unless you have a compromised immune system, though, antibacterial soaps and cleaners do more harm than good. Regular soap and water will get your house just as clean, without the negative side effects of antibiotics.

Another way that even healthy people ingest huge amounts of antibiotics is through their food. Conventionally raised animals are given large doses of antibiotics to make them grow faster and prevent infections that would otherwise occur in their crowded living conditions. Quite apart from the inhumanity of this system, the ubiquitous use of antibiotics is problematic to the health of the humans who then eat the meat. Antibiotic use in animals may contribute to antibiotic resistance in humans, or may give rise to entirely new drug-resistant bacteria. If at all possible, try to get meat from animals not treated with antibiotics: grass-fed meat and wild-caught fish might be expensive, but so is MRSA treatment. If the price tags at Whole Foods are out of your budget, look into money-saving tweaks like buying your meat directly from the farmer, participating in a cow share, or choosing organ meats over muscle meats.

When (and How) to Take Antibiotics

Despite the serious dangers of antibiotics, the cure is not always worse than the disease. The Bubonic Plague ravaged Europe in the 1300s, killing at least 20 million people. Untreated, plague is almost always fatal. Today, we can fight it with common antibiotics. Most people would rather suffer from disrupted gut flora than from agonizingly painful sores followed by certain death. Antibiotics also have less dramatic long-term benefits to society: after they came into general use following the Second World War, the average human lifespan increased by eight years. Thus, while they aren’t ideal, antibiotics have incredible lifesaving potential: they’re nicknamed “wonder drugs” for a reason.

If you take care of your physical health and have no other immune problems, you probably won’t need antibiotics very often. But most people will have to take antibiotics (or give them to their children) at some point; in this case, there are several important ways you can minimize the damage to your body while still getting the benefit of the drugs.

First, make sure you have an illness that actually responds to antibiotics. Many people pressure their doctors for penicillin when they have a cold or flu, but this is completely counterproductive because colds and flus are viral diseases. Viruses are dead; as their name suggests, antibiotics can only kill living bacteria. Therefore, penicillin is worse than useless against a cold. Don’t push your doctor for an antibiotic prescription unless you need one.

Second, make sure to take the actual medication correctly. Antibiotics work at an astonishing rate: within 8 or 10 hours, most people taking them for common diseases like strep throat feel almost entirely better. This is great! But it doesn’t mean you can stop taking the antibiotics. Continue to take the medicine exactly according to the doctor’s instructions – don’t give any to anyone else; don’t save any to use later. If you stop taking the medicine prematurely, the strongest bacteria may still be alive in your body; these bacteria can survive to re-infect you with a drug-resistant version of whatever you had before, requiring you to take a stronger antibiotic with more serious side effects. Never take antibiotics prescribed for anyone else.

As well as preventing drug resistance and unpleasant side effects by properly administering antibiotics, you should take proactive measures to minimize the damage to your gut flora. If you must take an antibiotic, either eat fermented foods (such as sauerkraut, kimchi and fermented dairy products like yogurt and kefir if you tolerate dairy well) or take a probiotic supplement to help restore the healthy bacteria to your gut. Probiotics don’t contain the whole range of healthy bacteria in the human intestinal system, but they’re better than nothing. During and after your antibiotic treatment, also try to stick to a fairly strict diet – allowing yourself the occasional treat is normally fine, but if your gut is already stressed by the antibiotic, try not to put any more pressure on it.

Potential Alternatives to Antibiotics

Alarmed by the growing prevalence of antibiotic-resistant infections, even scientists practicing conventional medicine are searching for alternatives to the escalating arms race between antibiotics and bacteria. As well as developing different strains of antibiotics, researchers have identified several alternative methods that could potentially replace antibiotic therapy altogether.

One of the most promising is fecal transplantation (technically known as Fecal Microbial Transplantation, or FMT), which is exactly what it sounds like. Since feces are largely made up of bacteria, a doctor can transplant a healthy person’s feces into the colon of someone suffering from intestinal problems; this quickly and safely recolonizes the ill person’s digestive tract with the normal variety and amount of human intestinal bacteria. FMT is far more effective than taking probiotics: while probiotic foods like yogurt or kefir are great, they only contain a few of the bacterial strains that live in a healthy gut; getting a transplant directly from another human being provides a much more comprehensive selection. Trying to replicate this diversity with a shelf full of probiotic supplements is like trying to get all your nutritional requirements by mixing and matching individual vitamin pills: theoretically, it could work, but it’s hardly the ideal method.

Fecal transplants have shown especially interesting effectiveness against antibiotic-resistant infections, most notably the hospital nightmare Colostridum difficile (C. diff). A long-term follow-up study also found that fecal transplants not only cure C. diff, but also help prevent recurrence later on, with no recorded side effects.

Unsurprisingly, many people resist fecal transplants because of the “ick factor.” And even if you’re interested in taking the plunge, it’s not the easiest procedure to obtain. Many doctors aren’t aware of it or don’t trust its effectiveness, several hospitals refuse to conduct the procedure in their facility, and few insurance plans will cover it. Home transplants are an option, but far from ideal. Nevertheless, since fecal transplants appear to be safe and effective, medical interest in the procedure has been increasing, and more hospitals may soon begin to offer them.

Another alternative is biofilm disruptors. A biofilm is like a bacterium’s coat of armor, protecting it from your immune system. Destroying biofilms can help your own natural defenses battle bacteria more effectively. Various different treatments can destroy biofilms – certain enzymes break them down, and other compounds can bind the minerals that bacteria need to maintain their biofilms. Biofilm disruptors can be helpful on their own, or in conjunction with antibiotics: one such compound caused penicillin to work 128 times as effectively, even against an antibiotic-resistant organism. A similar compound increased the effectiveness of another antibiotic, imipenem, against drug-resistant pneumonia. Thus, biofilm disruptors can help boost your natural defenses, and also increase the effectiveness of treatment if you do need to take a drug, sparing you from multiple doses of antibiotics and several of the harsher drugs. Restricting intake of the minerals that biofilms need (particularly calcium) is another option, but make sure to follow this with supplementation after you get well.

Various foods, especially spices, also have natural antimicrobial properties. Garlic, in particular, is widely available and appears to have measurable antibiotic effects. Although these foods are unlikely to be effective against a bacterial infection by themselves, they might do some good, and certainly won’t do any harm. Honey is another natural antibacterial agent – not when you eat it, but when you rub it on a wound. Colloidal silver is a very controversial remedy (before you decide to use it, make sure you spend some time researching the potential risks), but also commonly touted as an all-natural antibiotic.

Conclusion

As serious as their side effects can be, antibiotics are sometimes preferable to suffering the diseases that they can treat. A healthy adult who takes all medication correctly and proactively uses probiotic supplements should be able to withstand a course of antibiotics once every few years without serious problems. As alternative treatment methods like fecal transplants become more accepted, patients will hopefully have more options for treating bacterial infections and diseases; until then, the best way to approach antibiotics is to weigh the benefits and risks carefully for each specific case, and to reduce any unnecessary antibiotic exposure.

Leave a Reply