If you follow health-related news, you’ve probably noticed a recent spate of articles about food and the brain. But it’s always hard to really understand just one study or press release without any background about the area – after all, one study could just be a fluke. So here’s a slightly more in-depth look at the background to these studies, and what they mean in context.

Fast Background: Obesity and the Brain

Here’s a super-quick overview of what you should know about cravings, hunger, obesity, and the brain:

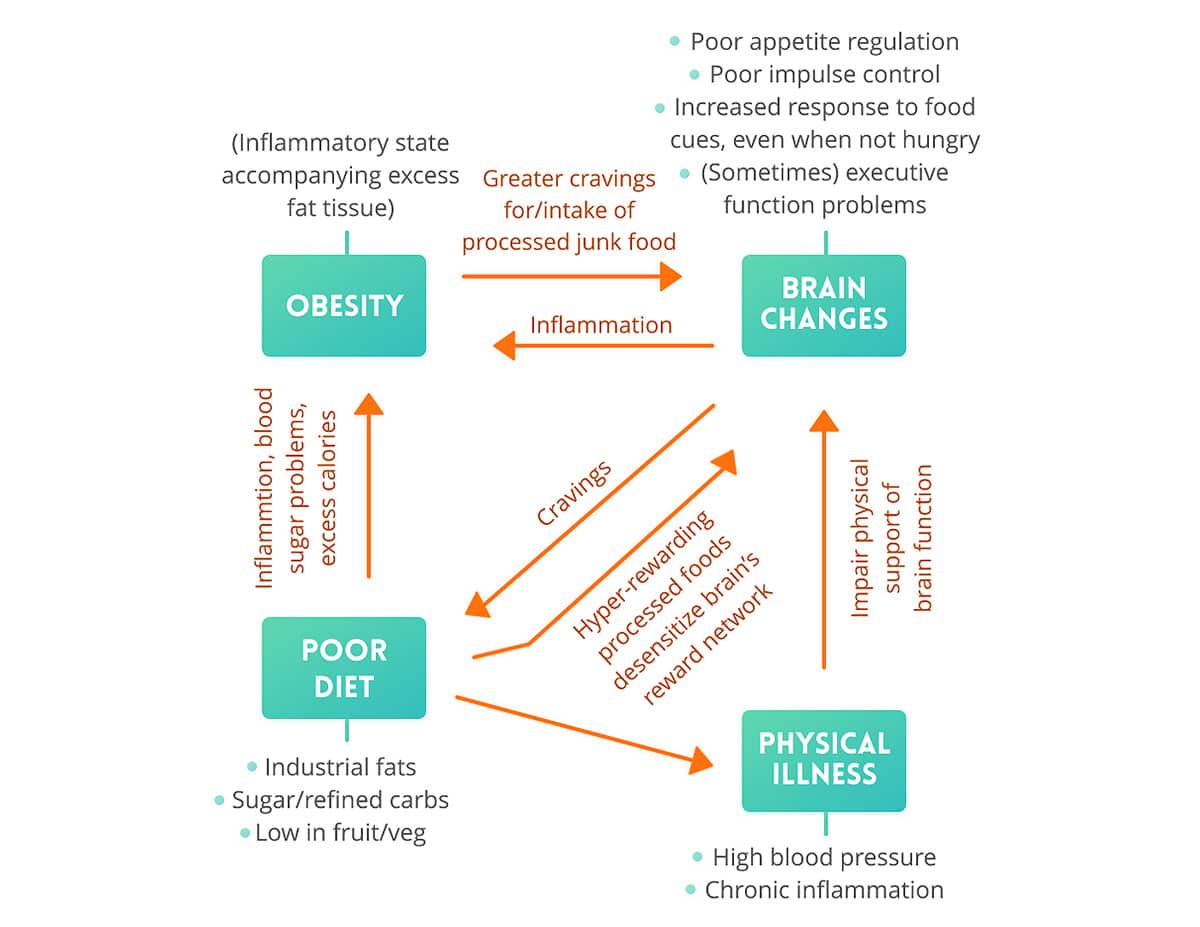

- Obesity is associated with changes in a brain area called the prefrontal cortex that impair inhibitory control. Inhibitory control is basically the ability to not do something even though you want to. Resisting food cravings is an example of inhibitory control. People with obesity have lower activation of inhibitory control, so they have a reduced ability to resist cravings.

- Obese people struggle more on some measures of executive function (like making decisions, planning, and solving problems), but results aren’t consistent.

- Brain changes in obesity also prevent normal appetite regulation. So people with obesity are (on average) more intensely hungry than naturally thin people.

- Obese people’s brains respond more strongly to food cues, even in the absence of physical hunger.

- Metabolic syndrome (which isn’t the same as obesity but often comes along with it) is associated with lower cognitive performance, especially during aging.

As for the causal connections underlying all those associations, if you look at the linked studies, they mostly support a network of connections that looks like this:

For more on food, obesity and the brain, try our series on food addiction (part 1, part 2, and part 3) or this look inside some actual MRI scans.

And Now, the News

And now for the actual news. Here are 3 new studies that just came out dealing with diet, obesity and the brain, and what they mean.

1. A typical American diet is associated with slower learning and feeling hungrier, probably for the same reason.

This first study wasn’t actually published as a journal article; it was a presentation

at a conference for food researchers. The scientists found that people who ate a typical junk-food “Western” diet did worse on a general learning and memory task than people who ate slightly better. This was connected to changes in the area of the brain called the hippocampus, which helps regulate memory.

But wait, there’s more! The scientists also looked at memories that were specifically related to food. One of the many things that the hippocampus does is help decide which memories are at the front of your mind. After you eat, food-related memories get a lot less vivid, because you’ve had enough energy now and your body doesn’t need to motivate you to eat any longer. Or at least, that’s how it’s supposed to work.

In the study, people eating the junk-food diet didn’t have less vivid memories of food after eating. So they still wanted to keep eating tasty food after their physical need for food was satisfied. This effect was associated with poor performance on the learning/memory task, so the researchers assumed it was all related to changes in the hippocampus.

The limitations: this was a study of association, not causation, so there’s no way to prove that the diet caused the brain changes. Maybe the brain changes were pre-existing for some other reason (genetics, chronic stress, sleep deprivation…all of those have a huge effect on memory), and caused the people to eat more junk food. But the study did cite some previous rat research suggesting that food might be the cause of the memory changes.

2. Obese women’s brains respond more strongly to food, even after eating.

That previous study was on eating a junk-food diet, which isn’t the same thing as weight (we all know thin people who eat junk all the time). This study looked specifically at weight. In the study, 15 lean women and 15 obese women did MRI scans before and after a meal. The researchers showed the women pictures of food, and while they were looking at the food, the researchers watched their brain activity in three areas: the neocortex, limbic cortex, and midbrain. The results:

| Lean | Obese | |

| Brain activity, before meal | High | High |

| Brain activity, after meal | Low | High |

In other words, the switch for “paying attention to food” didn’t turn off after a meal for the obese women. Normal-weight women are very aware of food when they’re hungry, but after they eat, they can think about other things. Obese women are very aware of food all the time.

This is consistent with previous studies of brain activity in lean and obese people, so it confirms a possible way that brain changes could be causal in obesity, as well as the other way around.

3. Brain stimulation has mixed effects for reducing cravings.

If brain changes can cause cravings, can brain treatments reduce them? A meta-analysis of studies published to date concluded…maybe.

A meta-analysis is a study that reviews and summarizes previous research. So the researchers here didn’t actually do any new experiments. Instead, they rounded up all the studies they could find on stimulating a part of the brain called the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex – did stimulation help reduce cravings and/or food consumption?

The researchers basically found that the studies were all over the place. Some of them showed an effect and some of them didn’t. They noted that studies where people eat in a lab might not really apply to real-world eating behavior, and called for more studies on people who get to eat in their houses like they normally do.

So What does it All Mean?

All this research about obesity and the brain is starting to explain one reason why “just eat less and move more” doesn’t work as a “solution” to obesity. We’ve been trying that for decades now, and regardless of whether or not people should be able to do it, the vast majority of people with obesity can’t. The growing number of studies on obesity and the brain are starting to suggest that there might be very powerful brain chemistry inertia going on here, making it almost impossible for people with obesity to “just” eat less.

But if you look back up the page, you’ll see that at least some obesity-associated brain changes are probably related to a diet of junk food. A diet of junk food is typically associated with obesity - how many brain changes in "obesity" are actually caused by the food, not the body fat? Probably not all, but probably at least some.

That’s where Paleo comes in. Instead of trying to eat less food (while constantly hungry), the idea of Paleo is to eat more nutritious food. Get all the good brain changes that you can from diet quality, and let that kick off a reinforcing cycle. If you believe the first new study up above, a better diet (not less, just better-quality) might help people feel less obsessed with food, which would lead to them automatically eating less, which would lead to weight loss and possibly a reduction in any problems caused directly by obesity itself. It sure sounds a lot more pleasant than starving it out on low-fat yogurt cups while daydreaming of a fudge sundae!

Leave a Reply